(Note: This article was originally published on May 5, 2021).

At Scaled Analytics (and even at my previous employers), I always told customers that THEY own the flight data that comes off of their aircraft. Today, I am no longer so sure.

This blog is a bit of a departure from my typical blog format. I am becoming more frustrated by a trend I have been seeing on the business jet side of aviation where the cost of implementing a Flight Data Monitoring or FOQA program is getting pushed higher and higher – making it a cost prohibitive pursuit for many operators.

And that is a real shame because we are only just getting the business jet operators to see the value of FOQA, even with their reduced fleet sizes.

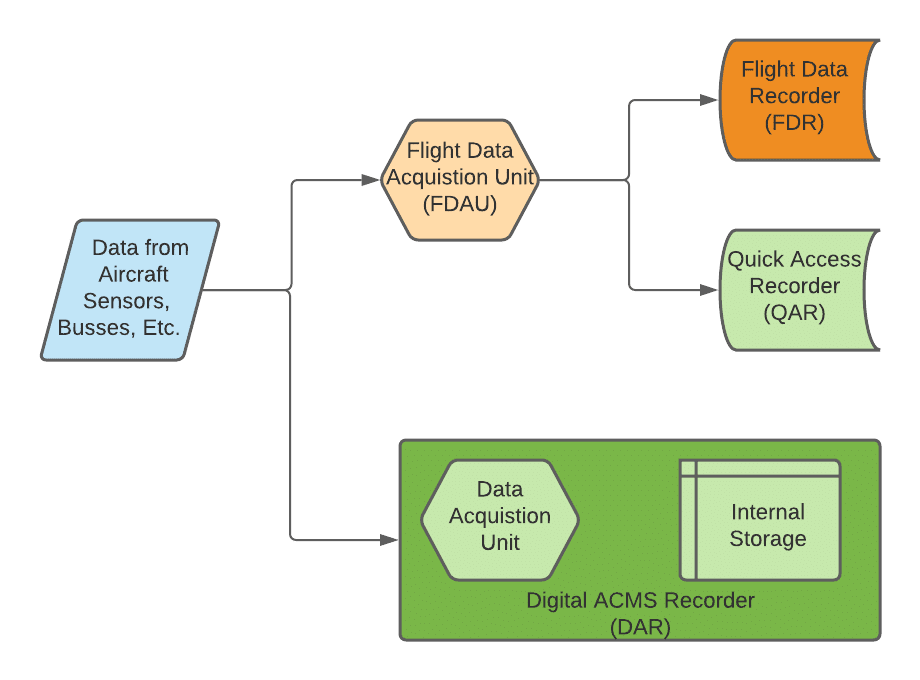

I will start my rant with a bit of a history lesson (I know, I know but this one is not that boring). Crash protected Flight Data Recorders (FDR) have been in use for decades, but it was not until the 1970s that the Quick Access Recorder (QAR) was introduced.

The QAR came to be because the FDR was (typically) difficult to access and it only stored roughly 25 hours of data (compared to a QAR that could store upwards of 400 hours). Otherwise, the QAR collected the exact same data that was sent to the FDR.

It was introduced in the interest of safety since proactive airlines wanted to make better use of their flight data to improve safety (i.e. Flight Data Monitoring and FOQA).

As these safety programs grew and the operators gained more experience, they wanted access to more data, but they were limited to what was available on the FDR. They could not reprogram the Flight Data Acquisition Unit without affecting certification, so the Digital ACMS Recorder (DAR) was born.

With a DAR, the operator could program the “box” to record whatever parameters they wanted (within reason) without affecting the FDR side of things and, therefore, certification.

This was a great option for those more progressive airlines with the budget, and it was not long before the data available on the DAR surpassed what was available on the FDR (to the frustration of air accident investigators, but that’s another blog).

But as the years passed, the parameters/data that was being sent to the FDR soon matched what was being stored on a DAR.

The DAR is still in use today and still serves a purpose for operators that want that control (and have the budget), but for most operators – especially smaller ones – the data sent to the FDR is quite sufficient so the QAR is back to being the recorder of choice today.

So, you may be asking, what exactly is the problem?

If you have read some of my other blogs, you may have heard of data frame documentation. This is a document that describes how the 1s and 0s stored on the flight recorder can be converted into meaningful engineering units like Airspeed and Altitude.

It is not, and never was, meant to be a means of encrypting the data. It just allows us to store data digitally on a recorder in an ARINC 717 standard format (ARINC 767 is a bit different, but you can read about it here if you are interested.) Some recorders (military, flight test) do encrypt data, but ARINC 717 is not about encryption.

This data frame documentation was historically part of the Aircraft Maintenance Manual (AMM) and still is for many aircraft – particularly transport aircraft. This made sense since, for continued airworthiness, data from the flight recorder needed to be checked once every year or two. The data frame document helped facilitate that, not to mention any other reasons why the operators might want to access and review their data.

In the case of the DAR, though, the data frame documentation was managed by the aircraft operator, since they programmed the unit.

The problem we are starting to see now, at least with some (but not all) OEMs in the business jet market, is that some OEMs are not including this information in the AMM but rather, are beginning to provide it separately and charge for it. A smaller number of OEMs are even taking the position that the data itself belongs to them – dictating permissible uses!

So where are we now?

Many that have been in this industry for some time welcomed the improved data volume available on the FDR in aircraft such as the 787, A380, and 737-NG. The DAR has some advantages, but being able to use a QAR with the same data stream as what is sent to the FDR made safety programs such as FDM much more attainable and easy to manage.

However, some of us in the industry worry that we are taking a step backwards and the business jet operator is the one that ultimately suffers.

We are already seeing new flight recorders come to market, such as those offered by Canadian company FLYHT, that have far greater capabilities than an FDR, such as flight following, satellite communications and real time maintenance event monitoring and reporting. These recorders were born, in part, because OEMs made it so difficult to access the data on the aircraft. These vendors offer a seamless solution to their customers that could not be provided elsewhere.

I was not in the industry in the 70’s or 80’s, but I would suspect those that were are seeing some similarities to the days when the DARs started to gain traction. At least today, it is much easier getting information from these third-party recorders than it was in the past.

These new recorder capabilities are great for the industry, but here comes the problem: as you might imagine, they are not cheap. Airlines and larger operators can, no doubt, benefit from their capabilities and easily justify the cost, but they may not make much financial sense to a business jet operator flying 400 hours a year.

After making strides to make FOQA affordable and feasible for business jet operators, we are coming full circle to putting a quality safety program financially out of reach for many of them.

Reputable FOQA or FDM vendors will simply pass this additional cost along to the operator. But some operators may not be able to afford that cost. This could persuade them to use less scrupulous vendors with “pirated” and potentially out of date data frame information in an effort to just “check a box” – doing absolutely nothing to improve flight safety.

So, if you are in the market for a new business jet and you plan on implementing a FOQA program, my suggestion would be to negotiate the cost of the data frame documentation into the cost of the aircraft. It might save you some surprises when you try to start your program.

If you do have the budget though, the new “third-party” flight recorders are very impressive, and they will remove the ambiguity once and for all over who owns the flight data – that should always be clear: YOU!

Let’s keep in touch

Sign up to get notified of new blog posts, videos or other news and information related to flight data.